Biblewhere

Offering thousands of unique online maps, plans, reconstructions, images, texts, essays, and documented treasures concerning or dating back to biblical and pre-biblical times, Carta Digital propels Carta Jerusalem's mission into the twenty-first century.

Welcome old friends and newcomers

Homeschooling

Let your children see the biblical past come alive. Expand their imagination, curiosity, and knowledge by exploring verses and vast biblical content that is linked to thousands of visual images, videos, maps and more.

Let your children see the biblical past come alive. Expand their imagination, curiosity, and knowledge by exploring verses and vast biblical content that is linked to thousands of visual images, videos, maps and more.

Sign up >

Students

Access the best visual Bible references. Connect biblical verses to historic, geographic and archeologic information to facilitate the writing of academic papers and gain insight into biblical events and reality.

Access the best visual Bible references. Connect biblical verses to historic, geographic and archeologic information to facilitate the writing of academic papers and gain insight into biblical events and reality.

Sign up >

Bible Lovers

Search, read, watch, listen, get inspired and gain knowledge of your favorite biblical verses, stories, events, and reality. Discover exclusive, visually-rich biblical treasures in geography, history, and archaeology.

Search, read, watch, listen, get inspired and gain knowledge of your favorite biblical verses, stories, events, and reality. Discover exclusive, visually-rich biblical treasures in geography, history, and archaeology.

Sign up >

Pastors and Faith Leaders

Enrich your sermons and inspire your community with thousands of exclusive, downloadable, and knowledgeable videos, articles, essays, photos, maps, images, plans, reconstructions and more.

Enrich your sermons and inspire your community with thousands of exclusive, downloadable, and knowledgeable videos, articles, essays, photos, maps, images, plans, reconstructions and more.

Sign up >Start your experience here

Kingdom of David

And when all the kings who were servants of Hadadezer saw that they had been defeated by Israel, they made peace with Israel, and became subject to them.

(2 Samuel 10:19)

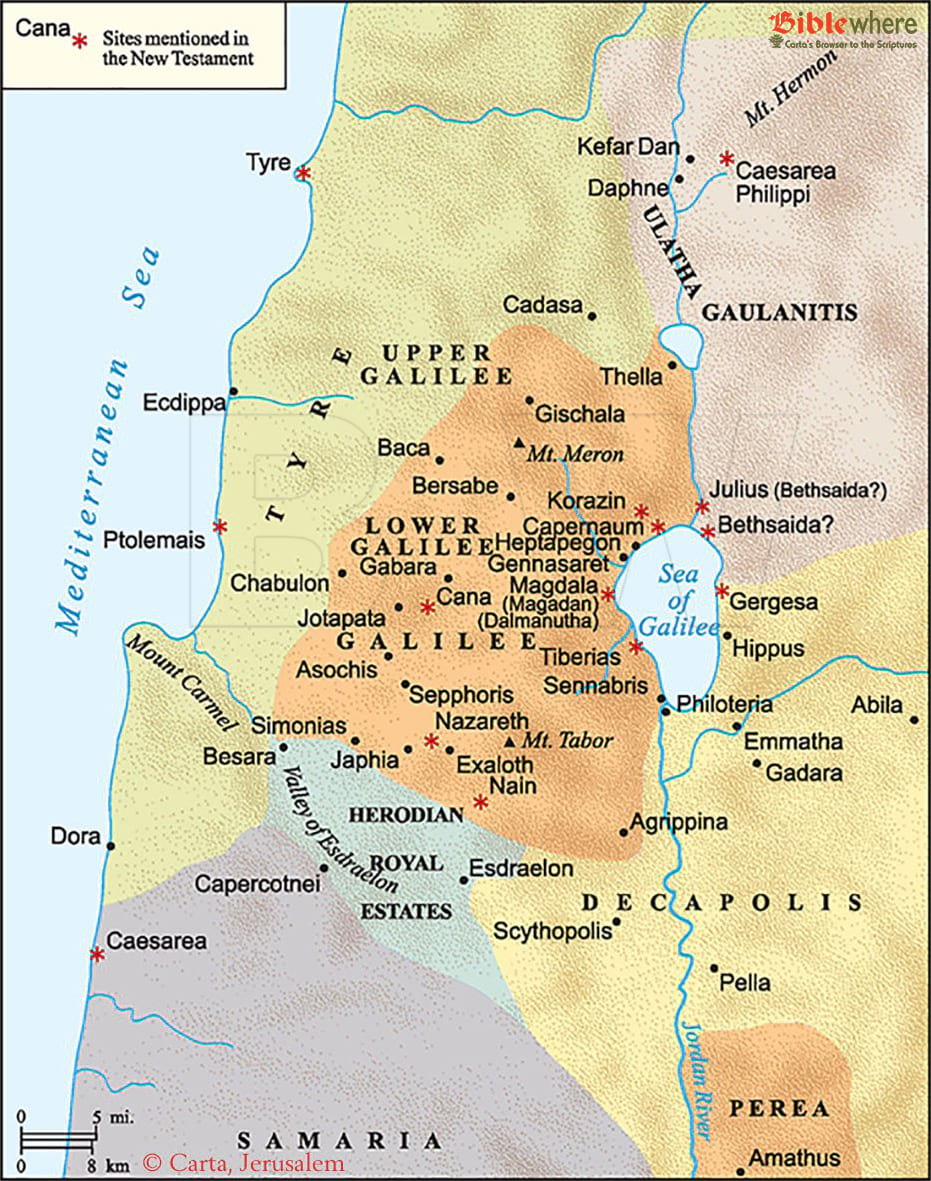

Jesus’ Galilean Ministry

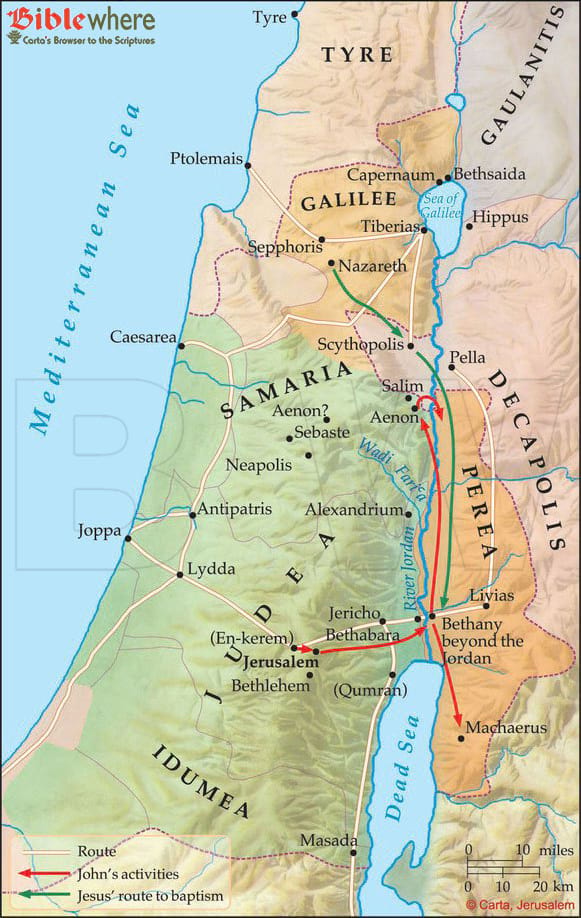

Jesus’ Galilean Ministry from Capernaum. It should not be supposed that Jesus’ move to Capernaum was an attempt to withdraw from the limelight and spend quiet time along the shores of a gentle sea. Rather, in the first century A.D. three distinct political units bordered the Sea of Galilee. By focusing his ministry around this sea, Jesus was able to come into contact with people who represented the full scope of religious, social and political identities found in first-century Palestine.

• Galilee proper, on the west side of the Sea, was under the control of Herod Antipas. Galilee included towns such as Capernaum, Magdala and Tiberias (Jn 6:23), Herod Antipas’s newly founded capital city (since A.D. 17). Galilee was primarily a Jewish region, with some corridors of Hellenism.

• Gaulanitis, rising from the northeast corner of the Sea, included Bethsaida and Caesarea Philippi. Governed by Herod Philip, Gaulanitis was an area of decidedly mixed Jewish-Hellenistic sentiments.

• The region of Decapolis touched the southeastern quarter of the Sea. This was an “in-your-face” bastion of Hellenism and Roman imperial might, established to guard Rome’s eastern frontier.

In addition, geographical, archaeological and textual evidence suggest that Capernaum, Jesus’ adopted hometown (Mt 9:1), was a bustling population center. The city lay astride the main highway linking Galilee’s coast to Damascus. Capernaum was the last town in Galilee before reaching Gaulanitis, and so it was appropriate that there was a tax office alongside the road (cf. Mk 2:14). Moreover, with at least eight large stone piers—the most of any town on the Sea of Galilee in Jesus’ days—Capernaum was a center of fishing and related industries (boat- and net-manufacture, fish processing and distribution). The outlying regions of Capernaum were devoted to agriculture, as was the case for every town and village in Galilee (cf. Mk 2:23, 4:1–9), but the city was also apparently a center for manufacturing heavy food-processing equipment such as grain mills and olive presses. Finally, a Roman garrison was based in Capernaum; its commander fronted the money to build the town’s synagogue (Lk 7:2–5). In all, it is certain that in Capernaum, Jesus faced the busyness and challenges of life no less than did his contemporaries. Occasionally, however, he withdrew in the early morning to “a lonely place” (Mk 1:35)—probably the rocky basalt hills above Capernaum—to gaze out over the awakening world of the Sea and pray in solitude.

Except for a few journeys, Jesus’ entire ministry before his final departure to Jerusalem took place around the northern half of the Sea of Galilee – also called the Lake of Gennesaret— (Lk 5:1); or the Sea of Tiberias— (Jn 6:1, 21:1; cf. Mk 2:13, 4:1). Here, along pathways connecting villages, in homes and in fields, Jesus found numerous illustrations for his parables of the kingdom, stories with teaching points grounded in everyday life (e.g., Mt 5:13–16, 7:13–23, 12:1–7, 13:1–52; Lk 13–16). Large multitudes from the entire area seemed to follow his every move; most were Jewish – from Galilee, Judea, Jerusalem, Idumea and Perea— (Mk 3:7–8), but others hailed from Gentile regions – the vicinity of Tyre and Sidon— (Mk 3:8). Initially, Jesus’ ministry focused on the “lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Mt 10:6), and so he sent his own disciples into the towns and villages of Jewish Galilee to preach, teach, heal (Mt 10:1–23; Mk 6:7–13) and, like him, to “go about doing good” (Acts 10:28). Eventually his ministry—and theirs—reached into Gentile areas as well.

Jesus performed most of his miracles in Capernaum, Bethsaida and Chorazin (Mt 11:20–24; cf. Lk 10:13–16), three towns forming a triangle on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. We can only surmise what most of these miracles may have been, since the Gospels mention only a very few in the vicinity of Bethsaida and none at all in Chorazim (cf. Jn 21:25).

The Gospels record several visits of Jesus to synagogues in Nazareth, Capernaum, Jerusalem and elsewhere (Mt 12:9, 13:54; Mk 1:21, 3:1; Lk 4:16; Jn 6:59, 18:20). We can assume that Jesus attended the synagogue every Sabbath, in whatever town or village that he happened to be in at the time. There is abundant literary evidence that many towns and villages throughout Judea, Galilee and the world of the Diaspora had synagogues during the time of the New Testament. Synagogues from the first century A.D. have been found at Masada, Herodium and Gamala, and a recently excavated building at Jericho that was probably a synagogue dates to the first century B.C. The synagogue was the main public institution for Judaism, where the community met every Sabbath day and on holy days to read the Torah and Haftorah (prophetic writings), to pray and listen to sermons or homilies. Jesus was often invited to read from the Scriptures and deliver the sermon when he attended synagogue. He soon gained a reputation for teaching “with authority” (Mt 7:28–29; Mk 1:22), with the result that he often locked horns with the local religious establishment (e.g., Mt 21:23; Lk 4: 16–30; Jn 9:22–23).

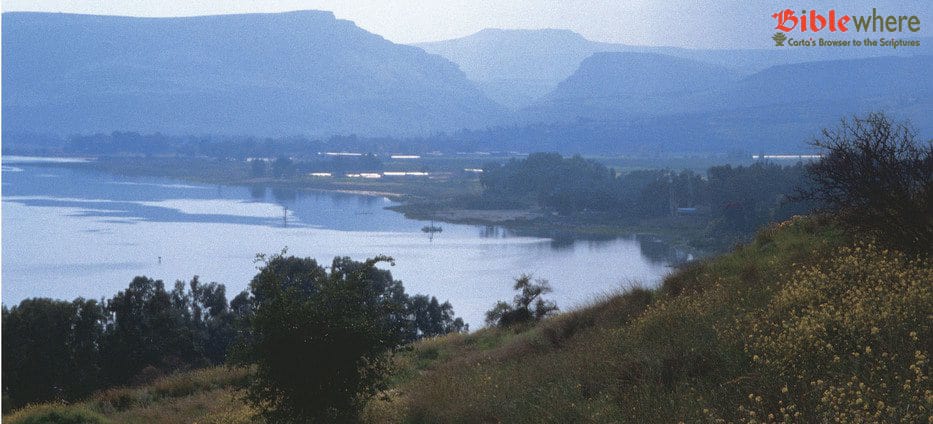

Jesus often traveled across the sea by boat and these journeys could end unpredictably, if, for instance, a powerful storm churned up the lake, a frequent occurrence during the winter months. While waves on the sea rarely exceed 1.5 meters (4 to 5 feet) in height in even the fiercest storms, Galilean fishing boats in the first century A.D. were not particularly large (the “Jesus boat” at Ginnosar, an Israeli kibbutz on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, measures 8 meters/27 feet in length) and could easily be swamped if heavily loaded. Such a storm caught Jesus’ disciples off guard one evening as they were sailing from Capernaum to the other side of the lake, probably intending to land, as they often did, in the territory controlled by Herod Philip (Mk 4:35–41). Jesus, asleep in the stern, was awakened by his frantic disciples and promptly calmed the sea, rebuking the evil chaos that ancient Israel had long pictured as deep, churning waters (Mk 39; cf. Gen 1:2; Ps 107:29; Jonah 1:4–16; Rev 21:1).

The boat reached shore in the country of the Gergasenes (Mt 8:28; Mk 5:1); some versions read Gadarenes or Gerasenes. While some scholars place the following event in the region of Gadara (a Decapolis city whose territory touched the southern end of the sea) or even in Gerasa (i.e., Jerash, another Decapolis city high in the Transjordanian hills), geographical logic suggests that the boat was blown into the harbor of Gergesa (modern Kursi), a small fishing village just on the Decapolis side of the border with Gaulanitis, Philip’s territory. Here Jesus healed a wild, animal-like man possessed by demons, sending the demons into a large herd of pigs which promptly ran down a cliff and were drowned in the sea—returning to the chaos, as it were, from which they came (Mk 5:2–17). A rather steep hill drops directly into the sea about 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) south of Kursi, providing a convenient location for the miracle. Jesus instructed the man whom he healed to spread the good news of God’s mercy to his gentile countrymen (Mk 5: 18–10), and the next time that Jesus returned to the Decapolis he was met by an eager crowd (Mk 7:31–37).

Tradition places the Feeding of the Five Thousand, the only Galilee miracle recorded in all four Gospels, at Tabgha (Heptapegon, lit. “seven springs”) on the northwestern shore of the sea near the Plain of Gennesaret. Certain textual evidence (e.g., Lk 9:10), however, suggests that this miracle took place in the vicinity of Bethsaida, on the sea’s northeastern shore. The location was a lonely, desolate spot, somewhat at a distance from any town or village (cf. Mk 6: 32, 6:36), yet within fairly easy walking distance from Capernaum (cf. Mk 6:3). While either of the two locations is possible on this account, the clues in the following episode (in which Jesus walked on water) suggest that the region of Bethsaida was the more likely location. It was the time of Passover (Jn 6:4), when the springtime grass was at its most luxuriant stage of growth (Jn 6:10). The five loaves that fed the multitude (Jn 6:9) were made from barley, the first harvest of spring. The yearly Passover celebration, a festival celebrating Israelite freedom from Egypt, fueled the Jews’ longing to be freed from Roman oppression. Perhaps it was this hunger that prompted those whom Jesus fed to proclaim him to be “the Prophet who is to come into the world” (Jn 6:14), apparently a reference to the coming prophet foretold by Moses (Deut 18:15, 18:18). It is noteworthy that Elisha performed a similar miracle, multiplying fresh barley loaves for a small crowd (2 Kgs 4:42–44); like the miracle at Cana (cf. Jn 2:1–11), Jesus again surpassed his predecessor.

Jesus’ disciples intended to return that evening to Capernaum by boat. Again a storm blew up, this one suddenly, as is typical in the unstable weather of springtime (Mt 14:22–33; Jn 6:16–21). While the disciples were straining to row westward against a strong west wind (Mt 14:24), Jesus came to them, walking on the water. Peter’s attempt to mimic his Master was thwarted by the fierceness of the storm and his own lack of faith. The boat landed on the Plain of Gennesaret where again Jesus was met by the needy multitude (Mt 14:34–36; cf. Jn 6:25).

Jesus’ travels took him to many towns and villages throughout Galilee (Mt 4:23; Lk 8:1), although only a very few other than those hugging the northern shore of the sea are mentioned by name: Cana (Jn 2:1, 4:46), Nazareth (Lk 4:16) and Nain (Lk 7:11–17). It was at Nain that Jesus brought back to life the only son of a widow as the lad was being carried out of the city for burial. Nain was a relatively small village on the northwestern slope of the Hill of Moreh, perched at the southern border of Galilee overlooking the Esdraelon (Jezreel) Valley. Eight hundred years earlier the town of Shunem had dominated the southwestern slope of the same mountain. It was here that Elisha had raised another son, also an only child, from the dead (2 Kgs 4:8–37). By the time of the New Testament Shunem was gone, but apparently the people of Nain still remembered the prophet who had visited their mountain centuries before. Upon witnessing Jesus’ miracle at the entrance to their city, the mourners exclaimed, “A great prophet has arisen among us! God has visited his people [again]!”

In addition to his visits to the Decapolis, the Gospels record only one journey of Jesus into Gentile territory: his trip with his disciples to the district of Tyre and Sidon (Mt 15:21–28; Mk 7:24–30). This journey probably took Jesus through a number of Jewish towns and villages nestled in the rugged hills of Upper Galilee, then into a very foreign land lying along the Phoenician coast. Here, as far from his “comfort zone” as Elijah was from his when he ministered to a poor widow and her son at Zarephath (1 Kgs 17:8–16), Jesus touched the lives of a poor woman and her daughter. In them, he found faith in the God of Israel among the Gentiles.

By: Paul H. Wright

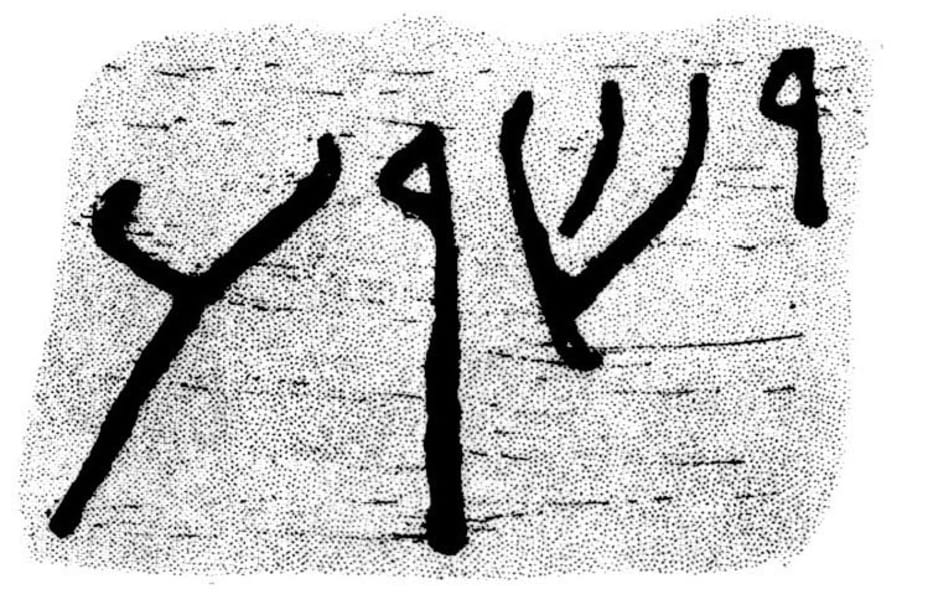

The “Sea of Galilee Boat”

(Matthew 8:23-27, 14:22-25; Luke 5:3; John 6:17)

The finding of the “Sea of Galilee Boat” is an amazing tale of vigilance, ingenuity, and persistence that led to the discovery of one of most significant finds for the Christian world. The story began with the dramatic recession of the Sea of Galilee in the nineteen-eighties. The recession exposed an ancient wooden boat lying at the bottom of the lake. Age tests found that it sailed in the Sea of Galilee in a period of special historical importance: between 50 BC. and 70 AD, the period in which Jesus was active in this region and in which the New Testament stories regarding his deeds and miracles in the Sea of Galilee took place. If so, then it was possible that this ancient wooden boat could be the “Jesus boat.” The discovery aroused great interest, not only because it was a historic artifact that fired the imagination, but also among botanists interested in the type of wood from which the boat was made.

The dramatic importance of the find made a number of agencies, led by the Antiquities Authority and the Ministry of Tourism, combine forces to extract it from the water. Upon its removal to the beach, a lengthy preservation operation began, after which it was transferred to its permanent abode in the “Yigal Allon Center” in Kibbutz Ginossar, close to the place where it was found. It should be pointed out that despite the interest the boat has aroused in connection with Jesus’ activities in the northern Galilee, the place has not become a “holy site” in the religious sense.

A Jesus boat is mentioned in the New Testament dozens of times to illustrate the deeds of Jesus in the northern Galilee and the miracles that took place there, described in the Gospel of Matthew:

“…And when he got into the boat, his disciples followed him: And behold, there arose a great storm on the sea, so that the boat was being swamped by the waves; but he was asleep: And they went and woke him, saying, ‘Save, Lord; we are perishing.’: And he said to them, ‘Why are you afraid, O men of little faith?’ Then he rose and rebuked the winds and the sea; and there was a great calm: And the men marveled, saying, ‘What sort of man is this, that even the winds and sea obey him?’”

(Matthew 8:23)

Questions were asked about the kind of trees from which the fishermen of the Sea of Galilee built their boats in the first century AD. Botanical scientists who examined the remains of the boat made the discovery that the boat builders were highly skilled. They learned that the construction was carefully planned, and twelve different types of wood were used for different parts of the boat. Most of the planks for the shell were made from Lebanese cedar. The ribs of the boat were made from oak, and ten other types of wood were used in its construction, including pine, carob, the Judas tree, the plane tree, the sycamore, the willow, the hawthorn, the jujube, the laurel, and the Atlantic pistacia (or terebinth). Today these trees, with their names inscribed, line a boulevard leading to the museum.

The planks that make up the skeleton of the boat and which are the strongest and most durable component of the boat, are from the trunks of the tree considered the sturdiest of the trees in the land of Israel, the oak. It has a special significance for Christian believers as a symbol of Jesus’ strength, and in Ginossar this tree gained additional importance as a building material for a boat in which Jesus sailed and from which he performed miracles. The gall oak is the largest kind of oak in Israel. It is an impressive tree with a wide treetop, and it can reach a height of forty feet or more. Because of this characteristic, in comparison to other types of oak trees, and although there is no clear indication of the type of oak from which the boat was fashioned, it can be assumed that the oak in question is the ”gall oak.”

By: Ami Tamir

S. Magal

S. Magal

David’s Early Years

The story of David and Solomon is inseparable from that of the rise of kingship in ancient Israel. Whoever aspired to rule all Israel in the 10th century BC faced two nearly insurmountable obstacles. Internally, the problem was a lack of unification among the tribes. The move from tribalism to monarchy carried enormous social, economic, political, religious and psychological ramifications, and was never completely made. Externally, the problem was weak borders, or, perhaps, a lack of realistic borders. The imperialistic Pharaohs of the Egyptian New Kingdom, who pretty much had had their way in Canaan throughout the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 BC), were in decline, and in their wake regional peoples such as Edom, Moab, Ammon, Aram-Damascus, Phoenicia and Philistia, in addition to Israel, found opportunity to express their own political and territorial ambitions. There was no simple answer to the question of how the Israelite identity, grounded to no small extent in a shared religious experience, would respond to and survive the challenges of tribalism and nationalism.

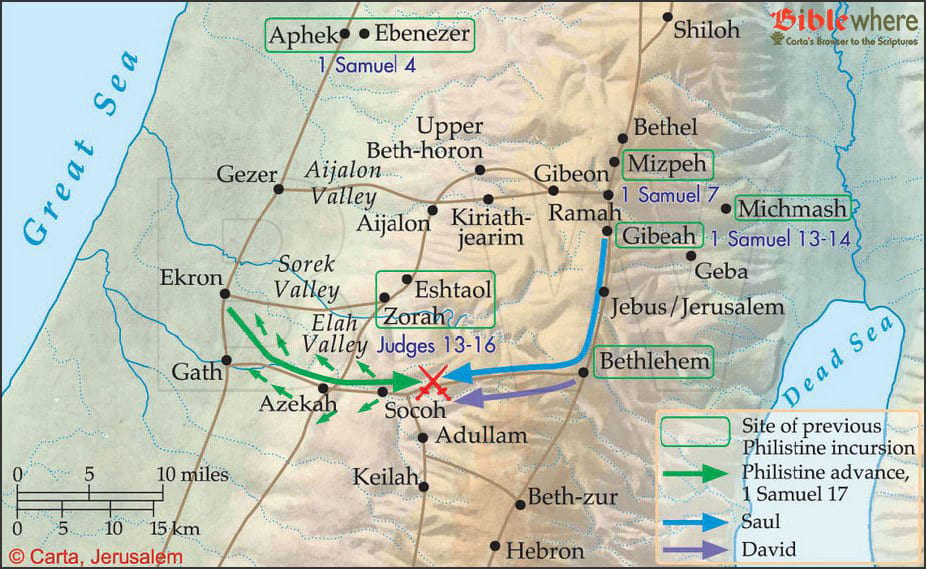

Over time the Philistines posed the most persistent external threat to several of the Israelite tribes, and heroes such as Samson, Eli and Samuel were generally effective in checking their advance into the central hill country (Judg 13–16; 1 Sam 4, 7:3–12). It was natural that Israel’s first king, Saul, was from the region of Benjamin, a Philistine “target” in the Israelite hills (1 Sam 9:1–10:27). All told, Saul’s actions as a national leader were a good start, but largely ineffective to the overall task at hand – cf. the further Philistine incursion described in (1 Sam 13:1–14:23). At God’s prompting, the aging Samuel chose David, of the tribe of Judah, as the next king (1 Sam 16:1–13). David represented a growing southern power base that included, among others, Simeonites (Josh 19:1–9; cf. 15:21–32), Kenites, Jerahmeelites, Calebites, Cherathites and Kenizzites (Josh 14:6; 1 Sam 27:10, 30:14).

David’s first appearance in the public eye came as a direct result of the Philistine pressure on Judah in the Shephelah. By taking the upper, Judean end of the Elah Valley from Azekah to Socoh, the Philistines laid claim to the two main routes into the mid-section of the hill country from the west, one heading to Hebron, the primary city of Judah, and the other to Bethlehem and, eventually, Gibeah of Saul (1 Sam 17:1). Unchecked, they could walk into both, and Judah’s viability as an Israelite tribe would be gone. Under-armed (cf. 1 Sam 13:19–22), undermanned (1 Sam 17:10–11, 16) and lacking the vision of the moment, Saul was paralyzed while David, with survival skills honed in the wilds of the Wilderness of Judah, defeated the Philistine hero in hand-to-hand combat (1 Sam 17:20–51). David’s victory over Goliath allowed Israel to push the Philistines out of the Shephelah (1 Sam 17:52–53); his greater triumph was to gain a reputation as a warrior and leader mightier than even king Saul (1 Sam 18:6–9).

Saul sensed that David’s star was rising, and the two began a game of dodge and feint played out on a personal level but with tremendous national ramifications. While for Saul David could be useful (1 Sam 18:17–19, cf. 14:52), he was also a threat that needed to be neutralized. For David, Saul was God’s anointed one (lit. “messiah”); (1 Sam 24:6; 26:9; 2 Sam 1:14) and should not be harmed, but at the same time David was not above forging alliances that strengthened his hand at Saul’s expense. David became the captain of Saul’s bodyguard (1 Sam 22:14) and also married Michal, Saul’s daughter, for love but also out of expediency (1 Sam 18:20–30). The situation was endemic to tension and jealousy, prompting a prolonged flight and chase through the hill country, foothills and wilderness of Judah, taking him more than once even into Philistia (1 Sam 19:1–27:12).

It is clear that David’s early experiences, both as a young shepherd and as a leader of men, strengthened his abilities, character and resolve to meet the more difficult challenges that he would face later in life. Many of the Psalms attributed to David speak of rough terrain, mighty rocks, strongholds and deliverers. David drew on a number of very tangible personal experiences to express his dependence on the power and provision of God in times of intense need (e.g., Psalms 18, 23, 31, 32, 37, 55, 61, 62, 63).

Israel’s King Saul and Crown Prince Jonathan both lost their lives in an action designed to push the Philistines, who were bent on assuming the role of Egypt’s heirs in Canaan, out of the Jezreel Valley (1 Sam 28:1–31:13). Worse yet, the Philistine action had cut the fledgling Israelite nation in two. With Israel on the brink of chaos, David pressed to seize control. First he was anointed king over Judah at Hebron by popular acclaim—one might say in triumph—and reigned from there for seven and one-half years (2 Sam 2:1–4, 11). Meanwhile, in Gilead Saul’s general Abner orchestrated the royal line of succession by proclaiming Ish-bosheth (Esh-baal); (1 Chron 8:33), the dead king’s son, as king “over Gilead, over the Ashurites, over Jezreel, over Ephraim, and over Benjamin, even over all Israel” (2 Sam 2:8–10). This list of place-names is telling: the house of Saul maintained control over the block of hills on either side of the Jordan River, but the northern tribes (Issachar, Zebulun, Naphtali and Asher), if ever under Saul’s command, were gone, as was Judah. David responded by waging a prolonged, and ultimately successful, civil war against the remnants of the house of Saul (2 Sam 2:12–4:12).

One of David’s first acts as king of all Israel was to relocate his capital from Hebron to Jerusalem (2 Sam 5:6–9). This was a wise political move on a number of accounts. David realized that Hebron was too far south geographically and too Judean culturally to give him credibility with the tribes in the north. Jerusalem (Jebus) had been allotted to the central tribe of Benjamin (Josh 15:8; 18:16, 28), yet remained a Jebusite (Canaanite) enclave deep in the central hill country. Although Saul’s Gibeah lay only five miles north, Israel’s first king was unable to, or uninterested in, bringing Jerusalem into the Benjaminite orbit. David redeemed the city and its holdings—thereby gaining favor among the people of Benjamin—but rather than turn Jerusalem over to them he maintained the city’s independence, transforming it into a capital for all Israel. The Jebusite fortress had been called the Stronghold of Zion; with its capture, Zion became the City of David, the royal seat of an Israelite national dynasty. Eventually Jerusalem would become one of the world’s greatest cities, a city of emotion, song, hope and praise, on the strength of its unique tie to God and the dynasty that He chose to represent His Name on earth – e.g., (Psalms 48, 121, 122, 125).

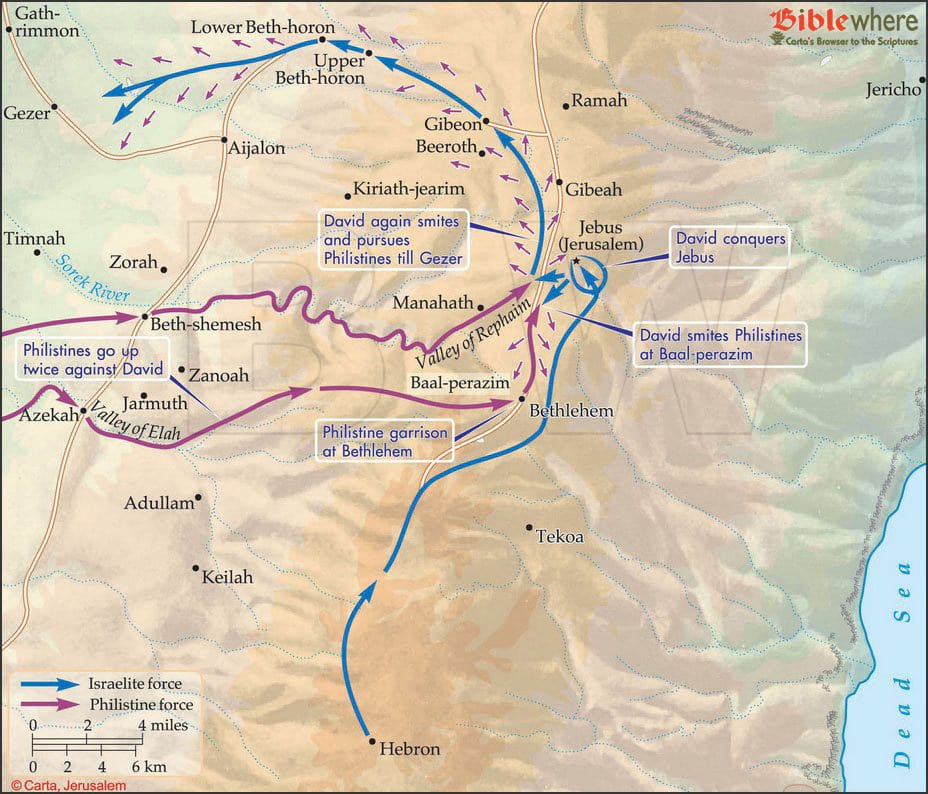

David’s move to unite the tribes of Israel at Jerusalem drew a response from Israel’s neighbors. Now that David was a bona fide player in the southern Levant, Hiram king of Tyre initiated commercial contacts which would eventually result in materials and manpower to build the Jerusalem temple (2 Sam 5:11–12). The Philistines responded to David’s conquest of Jerusalem too, but with a show of military force. Twice the Philistines penetrated the rugged hills west of Jerusalem and besieged the new Israelite capital from the Valley of Rephaim (2 Sam 5:17–25; cf. Josh 15:8); twice David flushed them out. With these victories and a follow-up campaign at Gath (2 Sam 8:1; 1 Chron 18:1) David had momentarily removed the Philistine threat. It can be assumed that Philistine control of the northern coastal plain and Jezreel Valley also fell to David, and that Israel was able to subdue old Canaanite urban centers of the region such as Beth-shean, Taanach, Ibleam, Megiddo and Dor in the process (cf. Judg 1:27–28).

By: Paul H. Wright

John The Baptist

The early part of the first century AD. was a fairly prosperous time for the Jewish residents of Judea and Galilee, all things considered, and a significant percentage of the population was learning to work within the Romanized political and economic systems that had enveloped their land. Still, many were looking for “the Elijah that was to come” (cf. Mal 4:5–6), though it was difficult to agree on exactly what his appearance would entail in real terms. When John the Baptist came “preaching in the wilderness of Judea, crying out: “Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand!” (Mt 3:1), dressed like the Elijah of old and playing the already ancient prophetic role to the hilt, he drew decidedly mixed reactions. It wasn’t exactly a bolt out of the prophetic blue—others also were claiming prophetic (or even messianic) roles (cf. Acts 5:33–39)—but John certainly cast a jarring counter-culture pose and in the end even gained the attention of Herod Antipas, the governing tetrarch. But for the writers of the Gospels John the Baptist was the real thing, the long-awaited flesh and blood arc spanning the chasm of time and binding the God-spoken Testament of Moses with the New Testament of the long-awaited Anointed One, Jesus the Messiah (Lk 16:16).

A role as special as this required a special kind of birth. Both of John’s parents, Zechariah and Elizabeth, were of priestly descent (Lk 1:5), a two-fold honor in the day. Luke describes them as “righteous in the sight of God and walking blamelessly in all the commandments and requirements of the LORD” (Lk 1:6); that is, devout folk living responsible lives with all proper public and private expressions of first-century Judaism in place. Zechariah was an active priest, one, it seems, for whom the priesthood was a sincere calling, unencumbered by the aristocratic tendencies that seemed to seize too many of his colleagues up in Jerusalem during the last years of the reign of Herod the Great. He and Elizabeth were well along in years but childless, and carried together the public stigma that God had withheld his blessing in spite of their lifetime of faithful service to him (cf. Lk 1:25).

Zechariah belonged to the priestly division of Abijah, one of twenty-four groupings of priests who served in the Jerusalem temple (Lk 1:5; cf. 1 Chron 24:1–19). Each individual from each of the priestly divisions had the opportunity to offer personally the daily incense offering in the temple, but because of the large number of priests this honor came only a very few times—perhaps only once— in a lifetime. After the incense was burned, the day’s officiating priest customarily lingered alone before the altar—just outside the door of the Holy of Holies—to bring his private petitions to God. In what was likely Zechariah’s last time to stand in this holy place, the chief angel Gabriel suddenly appeared and promised that not only would Elizabeth become pregnant, their much-awaited child would be a most special son, born in the ascetic, separatist tradition of the biblical Nazirites (Lk 1:8–15, 1:19; cf. Num 6:1–21; Judg 13:4–5, 14). Moreover, he would enter the world in the spirit and power of Elijah “to turn the hearts of the fathers back to the children and the disobedient to the attitude of the righteous, so as to make ready a people prepared for the LORD” (Lk 1:17; cf. Mal 4:6), indeed, be the forerunner of someone even greater than he.

Everything happened exactly as Gabriel said. Six months into her pregnancy Elizabeth had a special visitor: Mary, a near relative, who had also received an angelic visit and was in the beginning stages of her own divine pregnancy. The expectant mothers knew that something quite extraordinary was happening, and the two formed a special bond (Lk 1:26–56). So would their sons.

Nothing is known of John’s formative years except that he grew in body, mind and Spirit, like Samson and Samuel before and Jesus to follow (Lk 1:80; cf. Judg 13:24–25; 1 Sam 3:19; Lk 2:40). Luke identified John’s hometown as only a village in the hill country of Judea (Lk 1:39, 65), though church tradition has localized the site as Encharim, modern En Kerem in the far western suburbs of Jerusalem. The village is nestled in a wonderfully picturesque valley, far enough from Jerusalem to be surrounded by expanses of “open countryside” – so “deserts” or “empty places” should be rendered in Luke (Lk 1:80) in which a young John must have often hiked and explored. It was an optimistic landscape, mirroring the unbounded expectations that Zechariah had set for his one and only son (Lk 1:67–79).

Were it not for the unusual circumstances of his birth, John would certainly have followed in his father’s footsteps as the local village priest, serving dutifully in the Jerusalem temple as his turn came due, together with the next generation of priests of the division of Abijah. It is likely that he did so at first, before what Luke termed “the day of his public appearance to Israel” (Lk 1:80). Service in Jerusalem would have given John ample opportunity to see firsthand the excesses, insincerity and corruption that had come to infect too much of the Herodian-style temple leadership in his day. Certainly a righteous anger that was as pointed as John’s must have been honed on the anvil of personal experience.

Sometime in AD 28 or 29 (cf. Lk 3:1–3), when John was a little over 30 years old, he climbed over the Mount of Olives and withdrew deep into the wilderness of Judea, to the arid wasteland above the northern end of the Dead Sea. Traditionally, such wilderness areas were places of death, purification and rebirth (cf. Deut 32:10–12; Jer 2:6–7; Ezek 47:1–12; Hos 2:3–4, 14–20, etc.), and so the region formed an appropriate backdrop for the ascetic prophet. Something altruistic seems to have been involved, and the overall impression given by the writers of the Gospels depicts a man who was genuinely moved by the power-sanctioned injustices of his day, sacrificing his own reputation and career as a young priest to call the entire system into account. Priests tended to be members of The Establishment while Old Testament-style prophets usually stood counter-culture (beneath their wrathful front was a broken heart), and John’s divine call as the latter drove him from the comforts of home to a life of alienation in a place wild and alone. It was a willful move throughout, and this as much as anything likely prompted his former colleagues from Jerusalem to make the trek into the harsh wilderness to see what the fuss was all about. Those who made it down got an earful. It’s not easy to be called a snake by one’s (former) colleague (Mt 3:7–10; Lk 3:7–9).

With mixed doses of venom and sarcasm, John didn’t leave a lot of room for self-justification or philosophical discussions. What is surprising is not that Pharisees and Sadducees came to John in order to submit to his baptism (Mt 3:7), but that he dismissed them out of hand, likely sensing insincerity or mixed motives. But some people—perhaps many—did respond favorably. Luke calls them “the multitude” (Lk 3:7, 10; cf. Mt 3:5; Mk 1:5), the common folk who constantly fill the background of the Gospel story. Of those who were particularly moved (or who had little to go back to), some remained and became disciples; Elijah had had a school of prophets in the same area (2 Kgs 2:15). Most, however, certainly returned home to their families and jobs, changed for the better for the effort of seizing the grip that God had placed on their lives. One of these was Andrew, brother of Simon Peter (Jn 1:40); both would one day become disciples of Jesus.

John’s intended audience also included tax collectors and soldiers—collaborators and Gentiles who represented and enforced the everyday face of Rome (Lk 3:12, 14). His message to them was not that they should quit their jobs but that they should treat others fairly, righteously and honorably in the normal course of their duties (Lk 3:12–14). He demanded no more or no less of everyone else (Lk 3:10–11). John didn’t advocate political change; he only demanded that the political system—be it Rome or Jerusalem-based—govern benevolently (this was bound to anger both zealots and friends of Caesar). It was the Kingdom of Heaven that was coming (Mt 3:1), and for John, personally-changed lives that could influence society for good was the key to getting ready for it.

Those who responded by confessing their sins were baptized (Mt 3:5–6; Mk 1:4–5; Lk 3:3). While ritual acts of washing were common in Judaism in the first century AD, there must have been something particularly striking about John’s immersion, “a baptism of repentance for the remission of sins,” that gave him the nickname “the Baptist” (or, “the Baptizer;” Mt 3:1; Mk 1:4–5). John the Baptist made no mention of any of the priestly ceremonial rites that characterized either normative Judaism or the teachings of the nearby Qumran community, including the need to repeatedly purify one’s body through ritual washings. Instead, he made a direct connection between right living and a one-time immersion that signaled that the individual had adopted (or was in the process of adopting) a lifestyle characterized by acts of justice and righteousness, and had (or was) sincerely repenting of his sins. It was a bold, visible and decisive way of signaling the need for both Jews and Gentiles (everyone from Sadducees to Roman soldiers) to start over, as it were, from scratch (“don’t call yourselves children of Abraham…”; Mt 3:8). In essence, John’s baptism undercut an important cornerstone of Jerusalem’s temple apparatus (and of Qumran) in favor of direct access to God. It was, in the words of Mark, “the beginning of the gospel (lit., ‘good news’) of Jesus Christ” (Mt 1:1; cf. Acts 1:22, 10:37).

John didn’t exactly fit any of his contemporary modes—neither the Pharisees or Sadducees, not the residents of Qumran or the social or political critics of his day, not even the messianic hopefuls who, with the exception of Jesus, all looked for the overthrow of Rome. His message was religious, but with clear social and political implications. These implications were welcomed by the masses, although they seem to have been aimed particularly at people who held enough institutionalized power to effect real change. In spite of his clear ties to the mainstream Judaism of his day, perhaps the best way to characterize John is by the words of all four Evangelists – who quoted the Greek Septuagint text of Isaiah (Isa 40:3): he was “a Voice Crying in the Wilderness” (cf. Mt 3:3; Mk 1:3; Lk 3:4 and Jn 1:23).

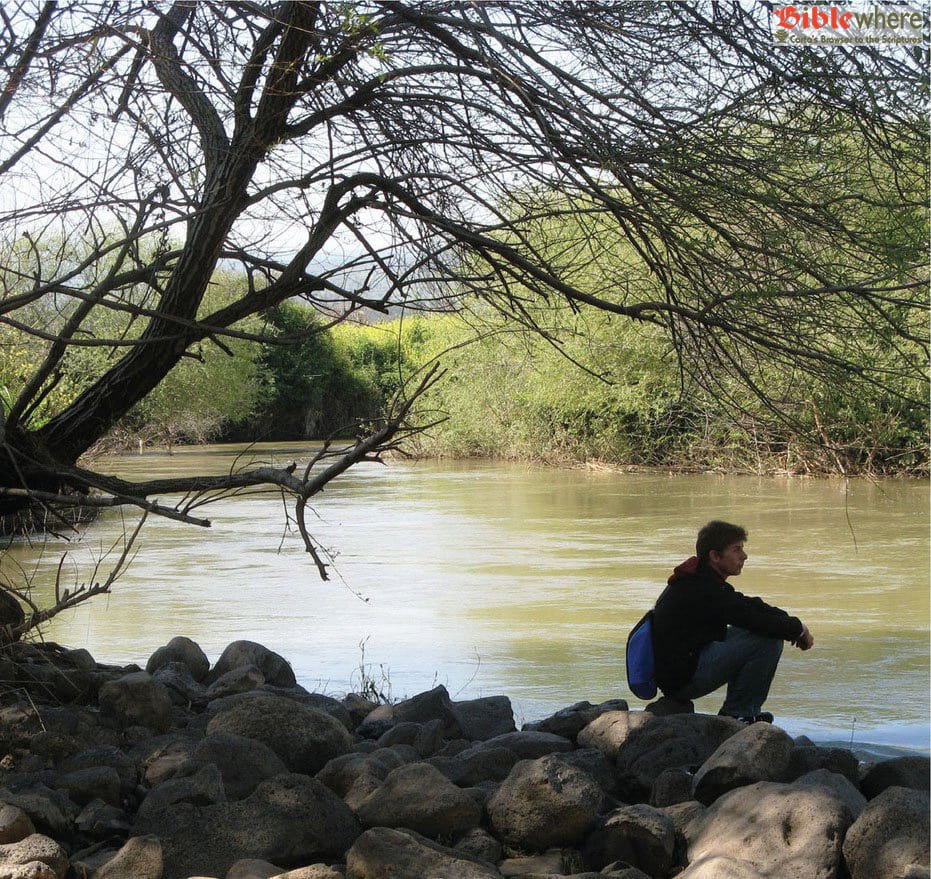

John’s prophetic ministry took him up and down the Jordan Valley, where he encountered many people on both sides of the river (Mt 3:1; Jn 1:28, 3:23, 10:40). It was a region that had been frequented by Elijah (1 Kgs 17:1–7; 2 Kgs 2:1–14); the two even ate off the land and dressed in a similar fashion (Mt 3:4, 11:18; Mk 1:6; cf. 1 Kgs 17:6; Zech 13:4; Mal 4:5–6). It was at Bethany beyond the Jordan that John met up with Jesus, his most significant candidate for baptism (Mt 3:13–17; Mk 1:9–11; Lk 3:21–22; Jn 1:19–34). This was the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry, and the climax of John’s. Jesus, who apparently had been watching John’s activities with keen interest from afar, came to the prophet from his home in Nazareth of Galilee. John seems to have known who Jesus was as well, although the realization that this was the one for whom he had been preparing the way now struck John with full force (Jn 1:29–34). He was at first put off by Jesus’ request to be baptized, then relented “to fulfill all righteousness” (Mt 3:14–15; cf. Jn 1:26–27, 30).

From this point on John fades from the scene of the Gospel story. He would have approved: “[Jesus] must increase,” the Baptist later told his disciples, “and I must decrease” (Jn 3:30). Understandably, some of them had trouble with the idea and were a little jealous of Jesus’ success which appeared to detract from the work of their own master (Jn 3:26). John could have solved the problem by simply disbanding his own ministry in favor of that of Jesus, since his specific calling had been to prepare the way for Jesus’ appearance in the first place. But he continued to preach and baptize to all who still would come, and Jesus even seems to have endorsed his ministry when he headed back into Galilee so as not to visibly override John’s work (Jn 4:1–3).

John’s prophetic ministry, in any case, could not have lasted much longer. Altogether it covered no more than a year (or two at the most) from start to finish. His work was cut short when he was arrested and put in prison—familiar ground for prophets, to be sure—ostensibly because of personal criticism of the conduct of the tetrarch, Herod Antipas (Mt 14:3–12; Mk 6:14–29; Lk 9:7–9). John publicly called Antipas to account for divorcing his wife to marry Herodias, the wife of his half-brother, Philip. John’s point could have been that Antipas’ divorce was foolish politically, since the tetrarch’s divorced wife was a powerful Nabatean queen whose territory bordered that of the tetrarch, but ramifications on the nation-state level didn’t concern the prophet. For the Gospel writers, Antipas was irked that John had held him to the same moral standards of everyone else. According to Josephus, Antipas feared that John the Baptist was growing too powerful among the masses and might launch a rebellion (Ant. xviii.118). Mixed motives are appropriate in regard to this multi-faceted prophet. John was beheaded at Machaerus (Ant. xviii.119), a Herodian palace-prison-fortress in Perea, near the Nabatean border, at a bawdy birthday party for Antipas.

John’s disciples were granted the right to their leader’s decapitated body and buried what was left of his remains with all the dignity they could muster in a location not mentioned by either the Gospel writers or Josephus. Despondent, they informed Jesus of the affair (Mt 14:12). To whom else could they go?

When John was still in prison, facing the cold stone walls and a diet that probably made him wish he had locusts and wild honey— not knowing if he would be executed although the grisly thought must have crossed his mind—he questioned whether or not this Jesus whom he had baptized really was the one who would vindicate the bold turn that his life had taken. Was it all worth it? Was Jesus going to pick up the pieces? Or would the momentum that was building for the Kingdom of Heaven stall out like it had when other messiah figures met an untimely death (cf. Ant. xiv.158–160; Acts 5:33–39, 21:38)? John sent some of his disciples to Jesus to ask if in fact he was the expected one. Jesus’ reply was the reply of the obvious: the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised up and the downtrodden are hearing the Good News (Mt 11:2–6; Lk 7:18–23). The coming Kingdom was in good hands. Then Jesus added, “Blessed is the one who doesn’t stumble over me.” This last comment wasn’t for John’s benefit, but the prophet’s disciples. What would they do if their master was gone?

And now he was, and John’s disciples had to make a choice. Some, such as the disciple Andrew of Bethsaida, brother of Simon Peter, attached themselves to Jesus’ growing band (Jn 1:35–42). Others probably scattered or went back home, as Jesus’ own disciples (including Andrew) would do soon after the crucifixion (cf. Mt 26:56; Jn 21:1–3). But some remained loyal to John; baptized by him, they followed and promoted his teachings and manner of baptism, fasting and prayer (cf. Mk 2:18; Lk 11:1). John’s movement remained alive and gained ground even outside of the land of Israel, in Egypt and in Asia Minor. Twenty-five years later, in the mid-50’s AD, the Apostle Paul met a group of around twelve people in Ephesus who believed in Jesus, yet had only been baptized according to the baptism of John. Apparently they had learned of John (and perhaps even Jesus) through Apollos of Alexandria, who had since moved on to Corinth (Acts 18:24–25, 19:1–3; cf. 1 Cor 1:10–13). How Apollos learned about John in the first place is not known, but the cosmopolitan Jewish community in Alexandria did have ongoing contact with Jerusalem, and an eloquent man such as himself may well have been well connected to channels of learning and thought throughout the Jewish world.

For many of the Jews of Jerusalem and Judea, John the Baptist was a rather pointed reminder that a life worth living was a life characterized by deeds of righteousness. For the emerging Christian movement across the Roman world, John was a bridge to Jesus. But for Jesus, John was a prophet—yet more than a prophet:

Truly, I say to you, among those born of women there has not arisen anyone greater than John the Baptist, yet he who is least in the Kingdom of Heaven is greater than he.

(Mt 11:11)

It’s quite an assessment for someone who made quite a scene during his lifetime. And it’s also quite an honor, comparatively speaking, for those who followed.

By: Paul H. Wright

Last Days of Jesus

All of the Gospels agree that the Romans crucified Jesus outside of Jerusalem. Roman responsibility for the death of Jesus is also recounted in one of the earliest Christian baptismal creeds: “[he] suffered under [the Roman prefect] Pontius Pilate.” Yet, the topographical and historical details surrounding Jesus’ execution vary in the reports of the New Testament. It is not possible to engage here the complex issues of the literary relationship of the four Gospels as historical sources for the Passion narratives. Much is written about the subject elsewhere. Our interest is more narrowly focused to determine what can be known of the physical setting of Jerusalem, and what that setting can inform us about the historical events that unfolded on it.

One hundred years of archaeological activity in Jerusalem, begun at the end of the nineteenth century, have helped to illuminate the physical setting of Jerusalem during the New Testament period. Questions still remain, but new data have provided fresh insights. The results have sometimes challenged long-held traditions attached to sacred sites. Nevertheless, a clearer picture has emerged about those fateful days. We shall attempt to sketch the historical framework for the events of that week, with particular attention given to their topographical setting.

Jesus approached Jerusalem in the days leading up to Passover (John 11:55). His pilgrimage continued a family practice. During the days of the Second Temple, it was not a necessary requirement to travel to Jerusalem three times a year as obligated at Sinai: “Three times in the year shall all your males appear before the Lord God” (Exod 23:17, 30:23). The impracticality of traveling long distances thrice yearly—particularly difficult from the remoteness of the Jewish dispersion—necessitated a figurative interpretation of the injunction, “to appear before the Lord” (Tob 1:6–10); Midr. Tanh. [Buber ed.] Tezawe 51b; (Ant. 4:203–204).

Nevertheless, Luke records the piety of Jesus’ family—“Now his parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the Passover” (Luke 2:41). Jesus’ familiarity with the setting of Jerusalem indicates he was accustomed to—and perhaps a familiar figure in—the city at the time of Passover, “The Teacher says, ‘Where is my guest room, where I am to eat the Passover with my disciples?’” (Mark 14:14; Luke 22:7–13).

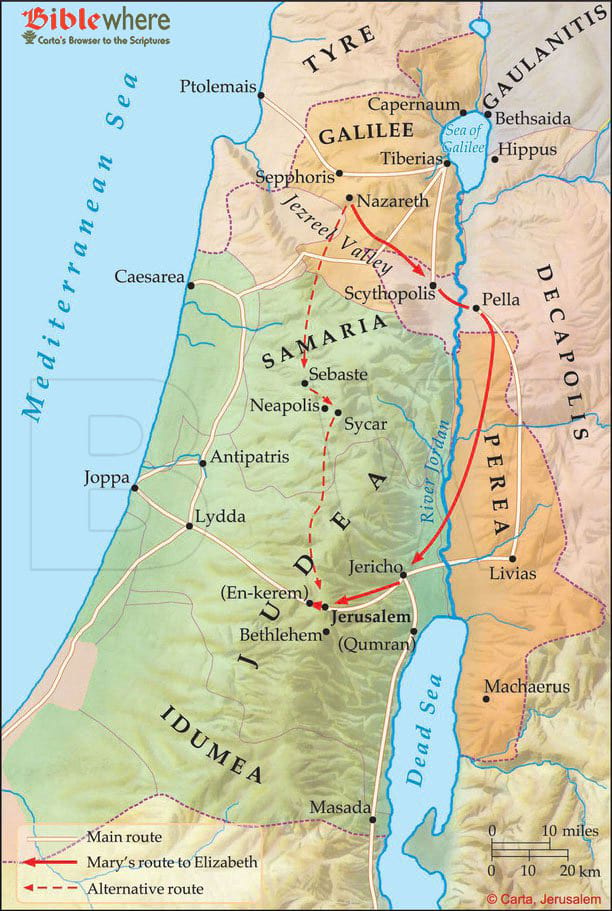

The northern ford across the Jordan River, which would have been used by a pilgrim who desired to travel to Jerusalem through Perea in the Transjordan, lay within the territory of Scythopolis (cf. Ant. 12:348). This independent Greek city was situated between the geopolitical regions of Galilee and Samaria. The city and its territory belonged to the province of Syria and were not part of the lands granted to Herod’s sons upon his death. As a statement of the geographical and political realities that existed in the days of Jesus, Luke’s description that Jesus “passed between Samaria and Galilee” in Luke 17:11 is correct and can hardly be deemed, as is sometimes charged to be, evidence of Luke’s “geographical ineptitude.”

According to the Gospels, Jesus did not always use the same route in his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Testimony on an earlier occasion (John 4:4–6) of Jesus’ presence in the interior of Samaria suggests that at times he followed the watershed route through the central hill country. This route was the most direct, taking only three days from Galilee to Jerusalem (Life 268–270). Yet, because of violence between the Jews and Samaritans, it was often considered too dangerous (J.W. 2:232–233; Ant. 20:118; Luke 10:30–37). A third route from Galilee mentioned in the ancient sources led along the foothills of Mount Ephraim to Antipatris and ascended the Beth-horon ridge to Jerusalem (J.W. 2:228). However, we have no mention of this route in connection with Jesus’ pilgrimages to the Holy City.

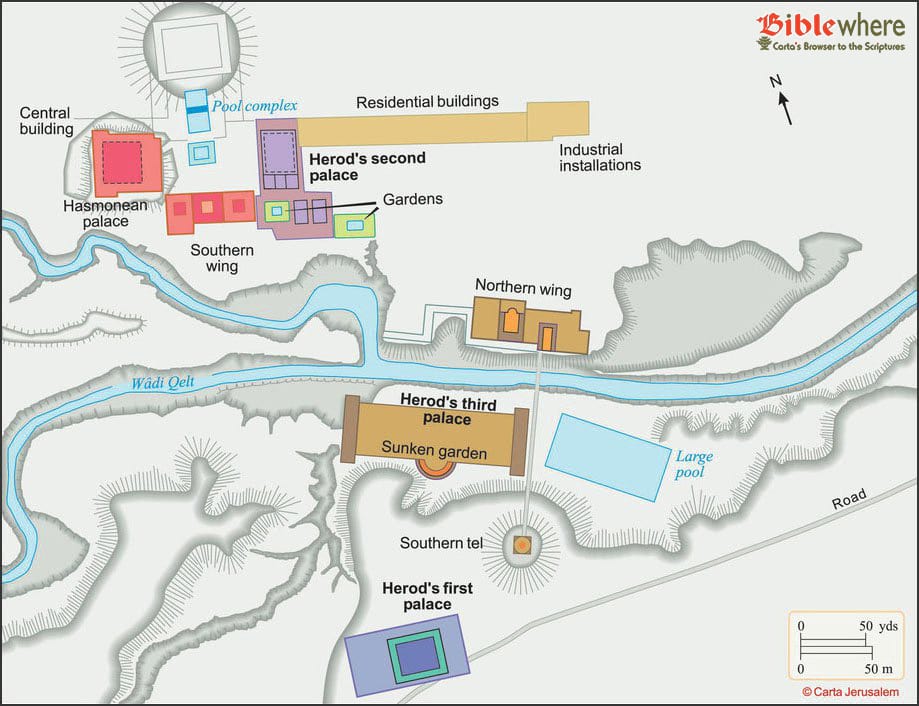

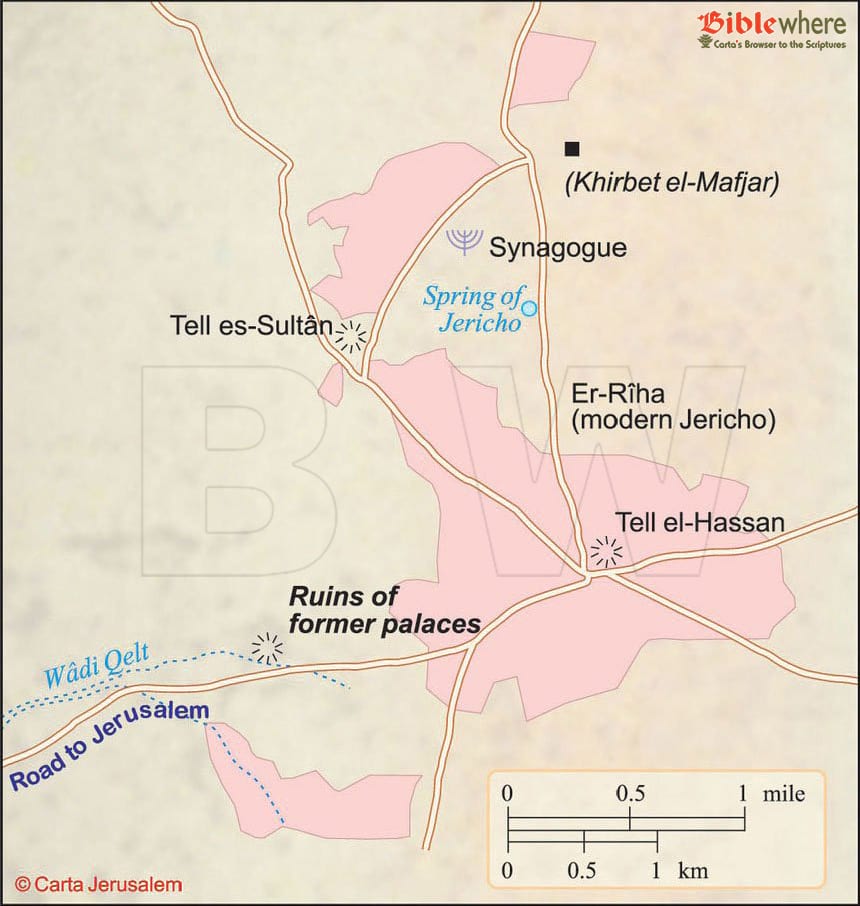

Mention of his travel through Jericho (Matt 20:29; Mark 10:46; Luke 19:1) indicates that Jesus’ pilgrimage from Galilee led him through the region of the Transjordan and along the Roman road from Jericho (cf. Luke 10:30) that followed near the biblical Ascent of Adummim (Josh 15:7). That route would have taken him within sight of the former Hasmonean and Herodian palaces at Jericho. Indeed, it seems that the physical presence of the former residence of Archelaus, son of Herod, may have been the cue for Jesus to adopt the well-known story of “the Herodian son who would be king” (Ant. 17:342–343; J.W. 2:111–113); Dio Cass. 55.27.6; Strabo Geog. 2.46, as the inspiration for his parable: “A man of noble birth went into a far country to receive a kingdom and then return” (Luke 19:12).

Only Luke relates that Jesus told the parable as they passed out of Jericho, and likewise only in the Third Gospel does Jesus use the story of the Herodian scion as the narrative kernel for his parabolic creativity. The collocation of the parable with strong historical allusions to the son of Herod and the magnificently restored residence that symbolized the royalty he sought but never attained, is remarkable. Recent excavations have determined that an earthquake destroyed the palaces in AD 48, and they were abandoned long before scholarship assumes that Luke wrote his Gospel. It seems the source for Luke’s unique combination of the parable and the physical setting of the environs of Jericho must have originated from a time when the palace still stood, or at least its memory was still fresh.

As Jesus approached Jerusalem he reached the eastern slopes of the Mount of Olives. On the outskirts of Jerusalem lay the villages of Bethany (Neh 11:32; Eus. Onom. 58:15) and Bethphage (Luke 19:29). The latter was positioned between Bethany and Jerusalem and marked the outer limits of the Holy City (m. Men. 11:2; b. Pesah. 63b). Its name was derived from the Semitic word for unripened figs (see Eus. Onom. 58:13) and may indicate agricultural activity in the vicinity (Mark 11:20). In the same vein, the toponym “Mount of Olives” (Zech 14:4) was also determined from local produce.

The New Testament records that Jesus stayed in Bethany (Matt 21:17; Mark 11:11), perhaps in the home of Lazarus, Mary and Martha (Luke 10:38; John 11:1). The large influx of visitors (cf. Ant. 18:313) during the pilgrimage feasts meant that many pilgrims had to stay outside of the Holy City (Ant. 17:213–214). Bethany is situated less than 2 miles (3 km) from Jerusalem (John 11:18), making it a convenient place for daily access to Jerusalem and the Temple. The Gospels portray Jesus’ trips back and forth between Bethany and Jerusalem (Mark 11:11–12). However, even pilgrims who stayed outside of the city were required to eat within the city walls the offering sacrificed on the Passover eve—14/15 Nisan (m. Pesah. 7:9, 7:12, 10:3). The disciples’ efforts to arrange the meal within the city walls of Jerusalem (Luke 22:7–13) are one of the clearest indications that for the Last Supper Jesus followed the rabbinic stipulations regarding the Passover meal.

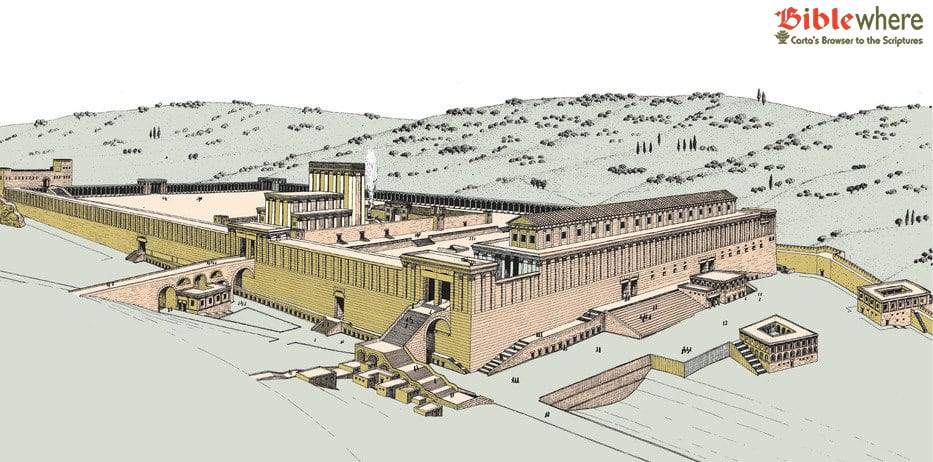

During the week leading up to Passover, Jesus was teaching daily in the Temple (Luke 19:47). Study of the Scripture within the temple precincts is recorded in Jewish tradition (m. Tamid 5:1; m. Yoma 1:7). It was also a place of study familiar to Jesus from his youth (Luke 2:48–49). The colonnaded porticoes surrounding the Temple likely included these places of study (cf. Acts 5:12). In addition, the platform atop the steps of ascent leading from the south into the Huldah Gates of the Temple Mount was a place where teaching was reported (t. Sanh. 2:2; m. Sanh. 11:2). The Mishnah describes three courts of law, “One used to sit at the gate of the Temple Mount, one used to sit at the gate of the Temple Court, and one used to sit in the Chamber of Hewn Stone” (Sanh. 11:2). The first of these locations may be identified near the broad platform atop the steps to the Huldah Gates.

It is in the vicinity of the Temple that Jesus challenged financial transactions that came under the responsibility of the Sadducean priesthood (Luke 19:45–46). Scholarship has tried to identify Jesus’ actions within the temple courts. The expanded narrative of Mark does imply Jesus’ actions were within the temple precincts and even directed against the Temple itself, “and he would not allow any one to carry anything through the temple” (Mark 11:16; cf. John 2:15). On the other hand, Matthew and Luke omit Mark’s portrayal that Jesus’ actions were aimed at the institution of the Temple, but instead at the priests entrusted with its care. Moreover, Luke’s verbal description does not necessarily indicate Jesus’ presence already within the temple precincts.

Luke’s account is supported by the Jewish sources. The mishnaic tractate Berakhot 9:5 states that one was not even permitted to ascend to the Temple Mount with a purse, let alone that it was the site of a marketplace: “He may not enter into the Temple Mount with his staff or his sandal or his purse.” It seems likely that Jesus’ actions took place either in the area of shops, recently excavated adjacent to the southern and southwestern walls of the Temple Mount, or the enclosed Royal Stoa (Ant. 15:411–416) in the southern portion of the Temple Mount. In an apocryphal story of the life of Jesus, we find him mentioned among the ritual baths near the shops south of the Temple Mount: “And [Jesus] took them and brought them into the place of purification itself and walked about in the temple” – P. Oxy 840; cf. (John 11:55; Acts 21:24, 26).

The cause for Jesus’ protest is not explicitly stated. A recent study of this episode in light of contemporary Jewish sources suggests that Jesus—like others of his contemporaries—objected to the House of Annas’ evasion of personal tithes to the Lord and oppressive measures. Jesus was certainly not alone in his assessment that this priestly clan (Luke 3:2; John 18:13; Acts 4:6) had misused its position as stewards of the temple finances.

The Sages said: The (produce) stores for the children of Hanin [=Annas] were destroyed three years before the rest of the Land of Israel, because they failed to set aside tithes from their produce, for they interpreted Thou shalt surely tithe…and thou shalt surely eat as excluding the seller, and The increase of thy seed as excluding the buyer.

[Sifre; cf. y. Pe’ah 1:6]

The description of the House of Annas being both “sellers” and “buyers” in Sifre may help to explain Matthew and Mark’s expanded description of the targets of Jesus’ rebuke. The Evangelists’ combination of sellers and buyers is a derivation from an earlier hendiadys. While Luke states that Jesus expelled only “the sellers” (cf. John 2:14), the other two Evangelists speak of “those who sold and those who bought.” The rabbinic witness suggests that in all of the Gospels Jesus is only concerned with the abuses of the temple hierocracy – see also Tg. Isa. 5:7–10; b. B. Bat. 3b–4a; (Ant. 15:260–262, 20:181, 20:205–207).

Jesus’ words and actions in the days leading up to Passover were interpreted as a challenge to the Sadducean temple establishment. Yet, his message shared a broad public appeal, and they could not arrest him openly (Luke 19:48). He gave voice to popular discontent (Luke 20:19), and a response by the temple establishment had to wait until a more opportune moment.

On the eve of Passover, preparations were made for the festive meal. While the priests offered other sacrificial offerings, Scripture stipulated that the people themselves were to sacrifice this offering in the Temple (Deut 16:2); m. Pesah. 5:6; Philo Spec. 2.145. The sacrifice could only be performed on the 14th of Nisan, and it was to be eaten that evening (Deut 16:6). The Gospels are silent on the details of preparation leading up to the meal, likely because they were so commonplace as to need no report.

By: R. Steven Notley

Explore the Holy Land Today

Sign Up Now

BibleWhere provides members online access anytime, anywhere and from any device to exclusive, invaluable, interconnected, fully searchable treasures that shed a new light on Bible lands and times. An amazing collection of written, drawn, illustrated, photographed, filmed and otherwise documented content. And yes, this already rich wellspring is growing by the day.